- Transformation Is Not Without Pain

- The Best Service Is No Service

- "Customer Service Can Be Emotional; Technology Cannot"

- "We Still Prefer Having People Help Solve Our Problems."

- Consumers Prefer Self-Service

- Human Interaction Is No Longer The Default

The discussion about which parts of customer service should never be automated has been rumbling on for a while. Ryan W. Buell, the UPS Foundation Associate Professor of Service Management in the Technology and Operations Management unit at Harvard Business School, published an excellent article on the topic.

Buell makes several arguments, highlighting the issues with the implementation of self-service, but there's also plenty of conflicting evidence. Are the automation sceptics missing something?

Transformation Is Not Without Pain

Buell points out that self-service and customer service automation do not always result in the benefits companies want. Often it's the opposite – with increased online banking uptake, many banks have seen a corresponding increase in customer service calls. He also cites an example where patients who were adopting e-visits to the doctor also paid more real-life visits to the doctor.

Technological maturity, information ambiguity, and consumer maturity using automated and self-service are mostly to blame. Most of these problems will disappear in time.

We shouldn't forget that where barriers to access disappear, customer service usage increases. Just think about how mobiles and smartphones have diminished access barriers to service. Call centres are always within reach with just a swipe of a screen.

So we should consider all these factors when planning to implement self-service and customer service automation. If you only look at gross numbers coming into a call centre, they might tell you that your efforts to reduce live contacts aren't working.

The Best Service Is No Service

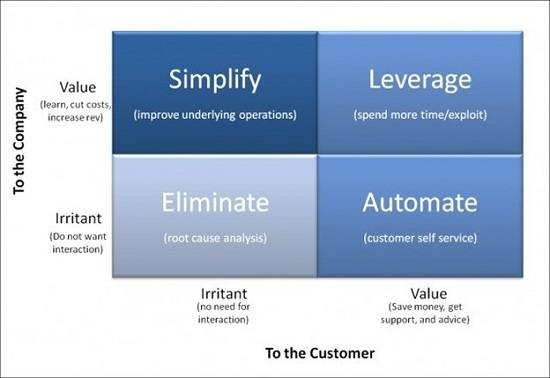

You should always make an effort to understand why customers are contacting you and the volumes that are associated with those types of contacts. And you should map these contacts in the value-irritant matrix you see below. Bill Price, former VP of service at Amazon, explained how they developed their contact strategy based on this two-by-two matrix insights.

Source: The best service is no service. Value-Irritant Matrix

When you do this, you can devise a strategy for each contact type, depending on where it sits in the quadrant. As you implement those strategies, you can easily track what's happening and explain any differences in contact volumes and their reasons.

You can debate whether automation is only a fit strategy for contacts in the right bottom quadrant. We believe automation (at least in part) should be part of the plan in each of the quadrants. In any case, this is a useful framework to help you design a contact strategy and track progress.

"Customer Service Can Be Emotional; Technology Cannot"

Secondly, Buell claims that technology can't be emotional, which must be a clickbait subtitle, because service and technology are not total opposites. Technology is one of the competencies required to deliver a service. So, yes, a service evokes emotions, and technology is partly responsible.

The point he's making is: "even if [technology] has the answers and can read the tone of our voice, or the expression on our face – people find the idea that technology "feels" and "senses" to be unnerving- and when a technology is deployed for such a purpose, the results can be unsettling." This is known as the uncanny valley:

The uncanny valley — the unnerving nature of human-like robots — is an intriguing idea. Both its existence and its underlying causes are under debate. We propose that human-like robots are not only unnerving but are so because their appearance prompts attributions of mind. In particular, we suggest that machines become unnerving when people ascribe to the experience (the capacity to feel and sense), rather than an agency (the ability to act and do).

When it comes to mimicking human behaviour, in our experience the uncanny valley effect holds when it comes to using avatars with human-like faces and "moving" expressions. They not only make us feel uncomfortable, but they also distract from the conversation itself. We humans expect technology to be functional and help us… not to be like us. This is also why we advise communicating clearly to users to signify when they're interacting with a chatbot.

But, it's also good to know that when bots express they are flawed, or do something unexpected yet planned, in a funny way, people love it. Maybe, over time, we'll be entirely at ease when it comes to mind-reading robots. Or perhaps we'll accept it in the same way we accept that much of the internet is free in return for our privacy?

"We Still Prefer Having People Help Solve Our Problems."

We disagree with Buell's statement here. Buell's main argument to support this claim comes from a 2012 research paper. As much as we believe the paper's facts, we don't think you can conclude that people prefer humans. The main conclusion is that people try to find other more effective ways to solve their problems if self-service doesn't help them.

There's also some convincing research that asks consumers whether they would like to interact with humans over machines or the other way around. Most of them conclude that many people prefer to deal with humans. But they seem to forget that people say one thing and very often do another. One of our clients even says it explicitly:

The unique thing is that in research, people say they prefer human contact over chatbots. We see them do the opposite.

And that's the thing. Year-on-year, we see interactions volumes with intelligent digital assistants, chatbots, etcetera, increase by over 50% on average.

Consumers Prefer Self-Service

We see the same trend with many of our clients. Done right, consumers love self-service. We even believe that they prefer self-service over live, human-powered service. But they want to have a human option available at any time. They know automation is not at a level where it can completely take over tasks or deal with all the possible individual variations. But if they could, they'd use automation without hesitation. They may say they wouldn't, but their behaviour says otherwise.

Human Interaction Is No Longer The Default

Despite differences of opinion, we mostly agree with Buell's four tips at the end of his article. If you haven't yet, it's worth a read. Because human-to-human interaction has always been the default, we've yet to discover the points where human-to-human interaction make the most difference. Now the scales have tipped in favour of human-to-bot interaction, we need to think about when humans should be designated.

Never assume there are parts of the customer journey that should never be automated. If you want to add real value to human-to-human interactions, your starting point should be exactly the opposite: making the most of human-to-human interactions and deriving maximum value from them, should be your priority.